Graptolites Radiolaria Stratigraphy

Stratigraphy

Paleozoic biostratigraphy

Graptolites are the most important faunal elements for biostratigraphic purposes in the early Paleozoic. They are used to define Global Stratotype Sections and Points (GSSP’s) for a number of chronostratigraphic time intervals from the early Ordovician to the Devonian. My research is mainly centered in three regions – Scandinavia (Norway, Sweden), Central Europe (Germany, Austria, Belgium, Albania) and eastern North America (Quebec, western Newfoundland) and in the time interval from the Cambrian (origin of the Graptolithina and Pterobranchia) to the Devonian (extinction of the Graptoloidea or planktic graptolites).

Taxonomic and biostratigraphic research at Mt. Hunneberg, (Västergötland, Sweden) resulted in the definition of a GSSP for the base of the second stage of the Lower Series of the Ordovician System (Episodes 27, 265-272). Mt. Hunneberg is a plateau mountain in south central Sweden. Here a 70 m thick dolerite sill protects the underlying early Paleozoic (Ordovician) succession from erosion.

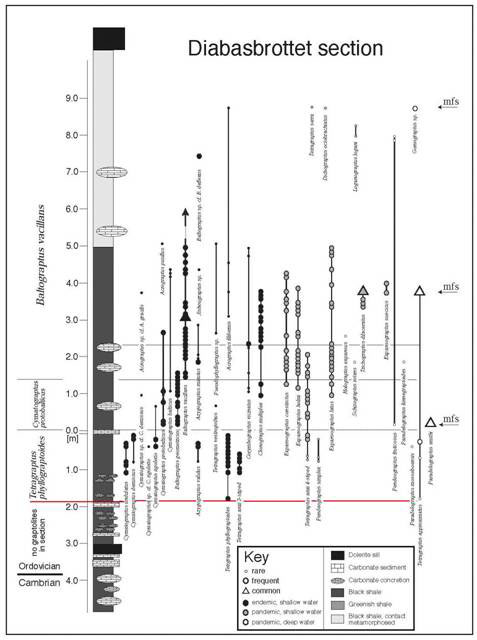

Figure

1. Diabasbrottet, Hunneberg (based on Egenhoff & Maletz, 2007, Palaios). Red

line shows the GSSP level at the first occurrence of Tetragraptus

approximatus. Graptolite ranges and frequency of occurrences are

shown.

Work in the Hunneberg sections of south-central Sweden and in the Oslo Region of Norway provides information for a model to recognize sequence stratigraphic boundaries in monotonous deep-water shale sequences using planktic organisms, mostly graptolites (Egenhoff & Maletz 2007). In these sections maximum-flooding surfaces can be recognized by distinct changes in faunal composition. It provides an excellent way of combining sedimentological and paleontological methods for stratigraphic purposes. It may also help to understand faunal differentiations based on ecological factors, facies relationships, understand extinction and origination rates and how they influence evolutionary patterns.

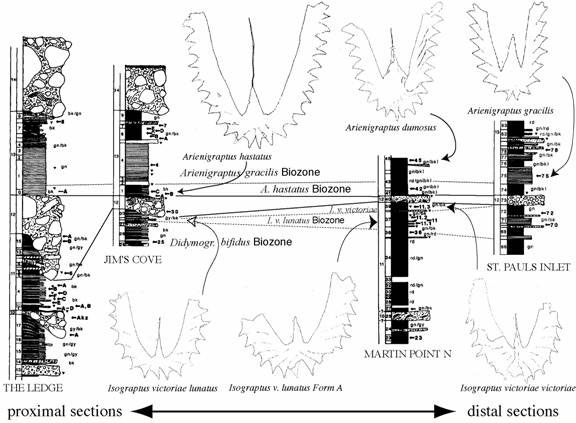

The isograptids in the mid-Arenig to mid-Darriwilian especially, show promise for both a phylogenetic analysis and a high potential for biostratigraphic purposes, as their proximal structures and rhabdosome shapes change quickly through time. Still, they are easily identified and differentiated when well preserved.

Figure

2. Isograptid biostratigraphy in the Castlemainian (early Middle

Ordovician) of the Cow Head Group of western Newfoundland, one of the

standard – and most complete - successions for Middle Ordovician

isograptids (Maletz et al. 2003).

Investigations of the Darriwilian (Middle Ordovician) in the Oslo region of Norway led to the recognition of a detailed biostratigraphy based on biserial graptolites. Many of the species are endemic to Scandinavia or represent Atlantic Faunal Province elements restricted to Ordovician cold water regions. The faunas are generally well preserved and retain considerable relief. Therefore they are highly important for taxonomic and evolutionary studies (Maletz et al. 2004).

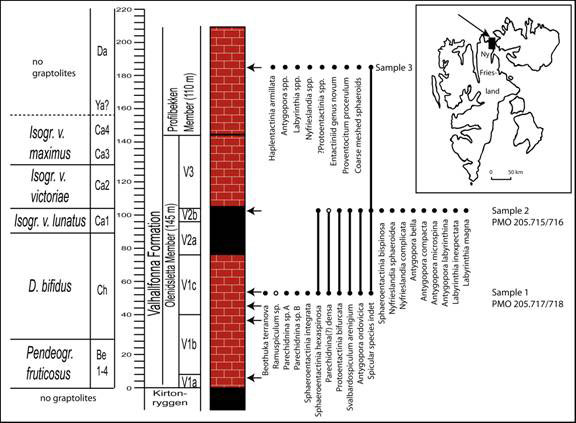

Recent work on faunas in western Newfoundland and Spitsbergen (Svalbard) showed the possible integration of biostratigraphic successions for graptolites and radiolarians, as well as other microfossils in these regions. Especially the Spitsbergen succession yielded a number of levels with radiolarians that can be correlated easily with the well-known graptolite biostratigraphy of the region. New radiolarian material was found in sections in Argentina (Precordillera), the USA (Vinini Formation, Viola Limestone) and western Newfoundland (Cow Head and Table Head Groups) and will provide important data to establish an Ordovician radiolarian biostratigraphy (Maletz 2007, Acta Pal. Sinica 46, suppl.).

Figure

3. Graptolite biostratigraphy and radiolarian occurrences of the

Valhallfonna Formation, Spitsbergen (based on Maletz & Bruton, 2005,

Geological Magazine).

Ordovician Basin Evolution

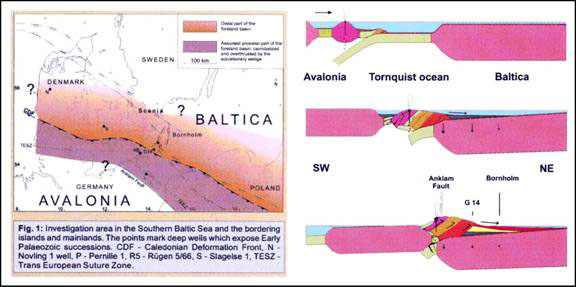

Research in central Europe concentrates on Ordovician and Silurian successions in Thuringia, Saxony, Vogtland, and north-eastern Germany (Ruegen drill cores, Baltic Sea). The Ordovician successions are poorly constrained by graptolites and thus, difficult to correlate internationally. The best graptolite faunal succession is known from the subsurface of north-eastern Germany, where a number of drill-cores encountered sediments interpreted as the accretionary wedge of a foreland basin that was thrust onto the southern rim of Baltica.

Figure

4. The southern Baltic Sea foreland basin (Beier et al. 1999).