GLY 103 (Field Trip) GLY 104 GLY 137 GLY 215 (Field Trips) GLY 216 (Field Trip) UGC 303 GLY 532

GLY 216- Paleontology & Stratigraphy

Field Trip

Devonian Stratigraphy and Fossil Assemblages of WNY

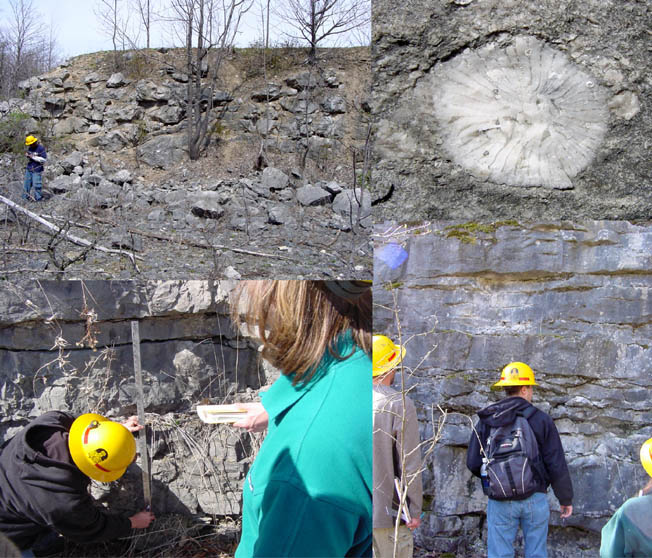

Figure 1. Buffalo Creek section at Bullis Road

(Stop #3) and crinoid fragments in Tichenor Limestone.

The geological underground of western New York State is mainly formed by Paleozoic rocks. These are slightly dipping towards the south, thus the oldest rocks are exposed at the southern shore of Lake Ontario, while the succession gets younger towards the south. Ordovician and Silurian rocks form the northernmost exposures, south of Lake Ontario. Major exposures of Devonian rocks can be found south of this region. Ordovician and Silurian rocks are also exposed in the Niagara River Gorge, and are the focus of the GLY 103 fieldtrip.

Generally, the trip takes place on the last weekend in April to ensure that the weather is moderate and the water level in Eighteen Mile Creek and Buffalo Creek is low enough to be able to investigate the rock succession without getting wet feet. Depending on the weather conditions, changes in the trip have to be considered, however, and not all localities may be visited.

General geological history of the Buffalo region

A large mountain chain, the precursors of the modern Appalachians, had begun to form during the Taconic orogeny, a mountain building event in the Ordovician Period. Through this orogeny, a mountain chain stretching from western Newfoundland in the North and as far South as Alabama, formed along the eastern coast of ancient North America, or Laurentia, as it is called. To the west of this mountain region, a vast shallow inland sea covered most of North America, from the modern Hudson Valley to the west until the – at the time non existent – Rocky Mountains and from Ontario in the North to Alabama in the South. This shallow inland sea was a warm water region at the equator enabling the wide distribution of rich tropical shallow water faunas: brachiopods, trilobites, crinoids, corals, bryozoans and ammonoids were common among other tropical Paleozoic faunal elements, represented by extensive fossil-rich carbonates and associated reef structures.

Following the Ordovician Taconic orogeny and its amalgamation of exotic terranes and island arc complexes deriving from far east in the Iapetus Ocean and glued onto the eastern margin of Laurentia, another orogenic event shaped the east coast of the continent. The Acadian orogeny in the Devonian further raised the mountain chains of eastern North America and shed enormous amounts of sediment into the inland sea to the west.

The Lower Devonian stratigraphic sequence of New York State is characterized by a succession of shallow water carbonates and to a lesser amount of darker shales accumulating in the region around the Hudson Valley. The dark shales may be interpreted to be deposited in a deep water region, along the axis of the Lower Devonian marine basin. This interpretation is also consistent with the location of the mountainous highlands of the eroding Taconic Mountains to the east. The presence of shallow water carbonates close to the region, however, indicates that these were already strongly inundated and did not represent an important source of extensive amounts of clastic sediments any more.

Figure 2. Map showing the distribution of

Devonian rocks in western New York State.

A similar depositional history is shown initially by the Middle Devonian rocks of New York State, especially the Onondaga Limestone. It represents a shallow water, high energy environment, rich in fossils. Then suddenly, the depositional environment changes in the later part of the Middle Devonian: Black shales of the Marcellus Group cover the tropical shallow water carbonates. This succession of dark shales on carbonates might be the first indication of the onset of the Acadian Orogeny towards the east. In the Acadian orogeny, Laurentia collided with the smaller continent of Avalonia. The remains of Avalonia are represented today by the exotic terranes in New England, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, as well as western Europe and Great Britain. Sedimentary histories and faunal associations indicate that these terranes originate from cooler water regions and show close faunal ties with Gondwana.

During the later part of the Middle Devonian the mountain uplift in the east caused the deposition of large amounts of clastic sediments in the shallow tropical sea. The basin was deepening through the enormous amounts of sediments delivered from the uplifted and eroding mountains and its load shed into the western seas.

In the

Upper Devonian clastic sedimentation continued in New York State. The

shorelines pro-graded from a position east of the Hudson Valley towards the

west and a foreland basin evolved. A large delta complex, the Catskill

Delta, formed at the shoreline. It was produced by a number of smaller to

medium sized rivers contributing sediments to form the large and

widespread delta complex, not by a single large river as does the modern

Mississippi River. The shoreline migrated towards the west during the

Upper Devonian and the Catskill Delta Complex reached western New York in

the Mississippian Period.

Overview of the visited localities

Stop #1. Abandoned Quarry, LeRoy, New York

Purpose of the stop: Observation of different facies types in a reef environment, taking detailed notes for research, measuring and describing a lithological section, collecting fossils and documenting their biostratigraphic distribution.

The locality is a large, abandoned quarry in carbonate rocks of Devonian age. In the quarry a Middle Devonian reef with its surrounding sediments is exposed. In the walls of the quarry, a succession of about 4-6 m of bedded carbonates can be investigated in some detail, forming an inter-reef sediment sequence. The LeRoy reef appears to rest directly on Silurian rocks, exposed on the quarry floor. This would mean that the Lower Devonian Bois Blanc Formation is not present in the region. There is an enormous age difference between the Upper Silurian and the Middle Devonian of about 20-25 Million years, therefore. This unconformity is only weakly expressed, as the sediments below and above the unconformity are in a horizontal position. The age difference can be recognized through determination of the fossils in both lithological units.

Figure 3. Rocks and fossils in the LeRoy Quarry in 2003.

Stop #2. Fall Brook, Geneseo, New York

Route 20A & Route 39, Bridge crossing Fall Brook, Geneseo, New York, Livingston County

The stretch of Fall Brook exposes the upper portion of the Middle Devonian (Givetian) Moscow Formation (Windom and Kashong Shale members) as well as the overlying Upper Devonian (Frasnian) Genesee Group. All units are rich in fossils and a diverse fauna including trilobites, brachiopods, ammonoids, corals, bryozoans and other can be collected during the trip.

The Leicester Pyrite Bed

The pyrite lenses of the Leicester Pyrite Bed are seen at the unconformable contact between the Windom Shale and the Geneseo Shale in the high north embankment north of the main falls. In this region, the Leicester Pyrite Bed carries a rich shelly fauna of diminutive species of brachiopods, mollusks, echinoderms and crustaceans.

Figure 4. The Fall Brook section in Spring

2003.

Stop #3. Buffalo Creek, Elma, New York

Bullis Road, Elma, New York, Erie County

Exposures in the creek bed and along west banks of Buffalo Creek, beneath the new bridge and on east bank about 300-400 m northwards (downstream) from bridge.

Exposures provide nearly continuous succession of upper Ludlowville and Moscow formations. The Ludlowville Formation at this locality includes the Wanakah Shale and the Jaycox Shale members. They are unconformably overlain by the Moscow Formation. The base of the Moscow Formation is a prominent ledge-forming unit, the Tichenor Limestone, followed by the thin units of the Deep Run Shale, Meneth Limestone and Kashong Shale members. Uppermost Moscow units, the Windom Shale and the Geneseo Shale are exposed upstream of the old Bullis Road Bridge along the east bank of the creek.

Figure 5. Buffalo Creek at low water level,

exposing the Tichenor Limestone in the water (left). The lower part of the

Moscow Formation is seen in the photo on the right.

Stop #4. Eighteen Mile Creek, North Evans, New York

Route 5 overpass of Eighteen Mile Creek, North Evans, New York, Erie County

This classic Eighteen Mile Creek section (section 7 in Grabau 1898) exposes portions of the Middle Devonian (Givetian) Hamilton Group and the Upper Devonian (Frasnian) Genesee and Sonyea Groups. The Wanakah Shale Member is overlain by the distinct Tichenor Limestone Member. The Tichenor Limestone is a thin, but widely traceable carbonate unit, which has been of considerable importance in establishing regional stratigraphic relationships within the Hamilton Group. At Eighteen Mile Creek, the Tichenor Limestone is a resistant, 30-40 cm thick ledge-forming crinoidal biospharite and biomicrite. It contains numerous large rugose corals (Heliophyllum, Eridophyllum) and heads of the tabulate coral Favosites hamiltoniae, large crinoid columns, fenestellid bryozoans and brachiopods. The large bivalves Plethomytilus, Actinopteria, and Goniopora, are locally abundant in the upper surface of the Tichenor Limestone.

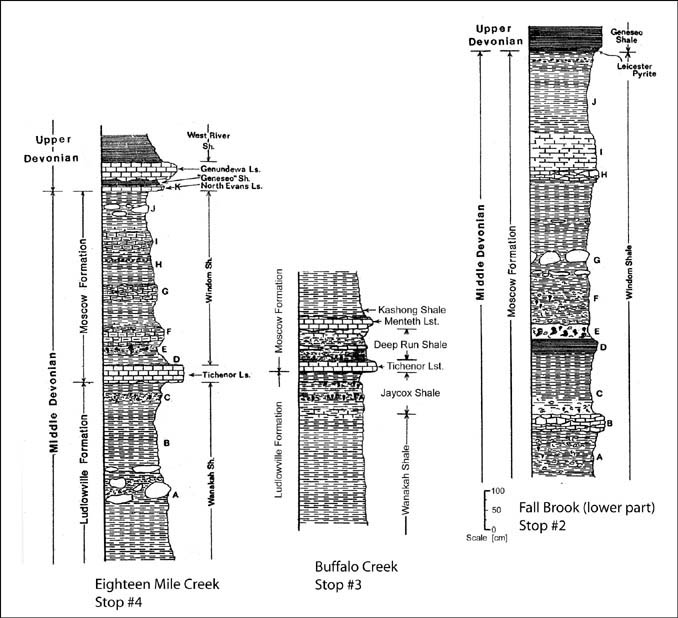

Figure 6. Lithology of the Fall Brook (Stop

#2), Buffalo Creek (Stop #3) and Eighteen Mile Creek (Stop #4) sections.

The Tichenor Limestone provides an excellent example of a condensed sedimentary unit. Many fossils within the limestone exhibit abrasion and/or faceting suggestive of long term exposure and reworking by current or wave action. Both contacts of the Tichenor Limestone are unconformable. The base of the unit exhibits a sharp erosional contact with the underlying Wanakah Shale. Undersides of Tichenor Limestone ledges are typically irregular, coated with pyrite and contain abundant large prod marks and hypichnial trace fossils.

Stop #5. Mouth of Eighteen Mile Creek at Lake Erie.

At its type locality north of Eighteen Mile Creek along Lake Erie shore, the Wanakah Shale consists of about 19.8 m of medium gray, soft, fossiliferous shale and shaly mudstone with several calcareous bands and zones of larger concretions. The highest beds of the Wanakah Shale exposed just below the Tichenor Limestone contain a high diversity fossil assemblage termed the Demissa and Stictopora beds of Grabau (1898, 1899). These units yield over 80 species of macrofossils and are particularly rich in brachiopods and bryozoans.

Figure 7. The shore of Lake Erie in the

afternoon. The steep cliffs show excellent exposure of Devonian rock with

a multitude of fossils (see well preserved corals on the left from this

locality).

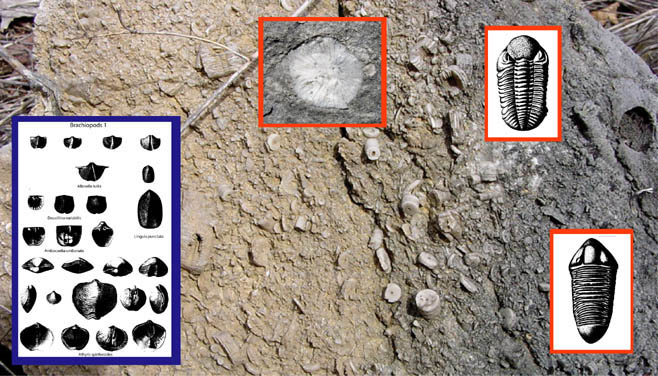

Fossil collection is not the main purpose of the fieldtrip, however, we cannot avoid finding them. So we often end up in collecting more than we need as they are so common and well-preserved. The most common fossils on the trip are the crinoids. Pieces often make up whole rock layers, but complete echinoderms are extremely rare and even longer pieces of the stems of sea-lilies are not too common. Usually only individual plate are found as the echinoderms quickly disintegrate after death. Obviously corals are abundant, especially small horn corals, but in the quarry (stop 1) many large tabulate corals may be found. Sometimes they are preserved in situ (in life position) in the reef area and we find great pieces. Brachiopods are extremely common in many shale layers and can be collected at the shore of Lake Erie, where they are weathered out of the shale. Trilobites are a bit more tricky. They are usually fragmented, but with a little effort, complete specimens can be found on the trip.

Figure 8. Some of the fossils that might be collected on the trip. The

background is made by a slab of limestone crowded by crinoid stem

fragments from the LeRoy Quarry. Brachiopods (left) and trilobites (right)

are common, as are corals (rugose coral on photo in center).

Officially the fieldtrip ends at about 5:00 PM and we return to UB. However, if the weather allows we have a barbecue (prepared by the students) at the shore to watch the sunset and to enjoy a nice evening out. So be prepared to stay a little longer than on your usual fieldtrip. It will be a great experience.

Figure 9. Sunset at Lake Erie, GLY 216 Fieldtrip April 2006.

Due to weather conditions in April we might not be able to access all localities. So the route might change a bit. Some of the localities are difficult because of high water levels, especially when the snow melts late and river levels are higher than usual.

GLY 216: Soft Rock II: Paleontology and Stratigraphy (w/Lab)